Napoléon on his shrimp, hunting the famous Marengo chicken, 14th June 1800.

Napoléon Bonaparte was a general during the French Revolution, who rose to become emperor of the French (empereur des Français), conquered most of Europe while opponents in Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia declared him “an enemy of humanity”.

Without doubt there was a before and an after the Empire in the history of the French Gastronomy. Although Napoleon was not a great lover of gastronomy, he was perfectly aware of the importance of the fine dining in the practice of politics and diplomacy.

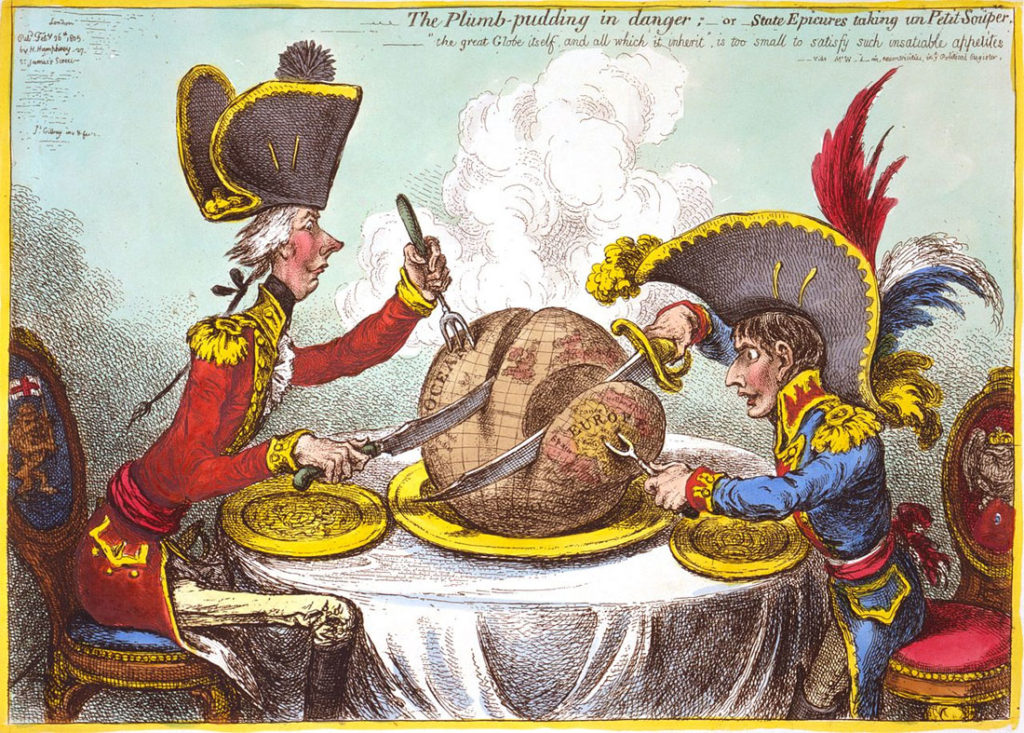

The Plumb-pudding in danger, or, State epicures taking un petit souper, by James Gillray (1756-1815). CREATED/PUBLISHED: London : H. Humphrey, 1805 February 26.

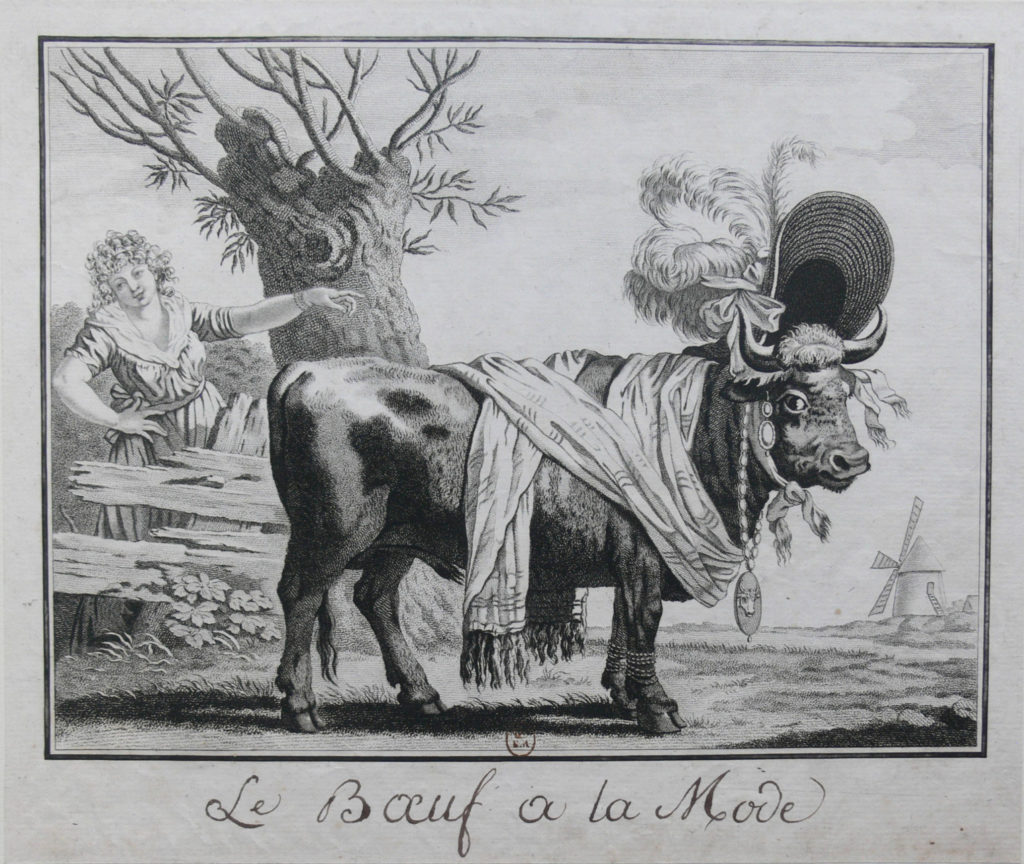

Le boeuf à la mode, by Louis-Charles Ruotte (1754-1806?) after Frans Swagers (1756-1836), Stipple engraving, 1797 © Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Department of Prints and Photography.

Napoleon had the good idea to use fine dining for his politics and his diplomacy as soon as he found himself in the position to govern or to negotiate. Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès (1753-1824) and Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754-1838) were the most zealous emissaries devoted to this task.

Talleyrand, nicknamed the Lame Devil, first known as a priest – whose libertine escapades and relative integrity contradict a possible natural inclination towards religious principles – was undoubtedly an outstanding diplomat, perhaps one of the greatest in History, as well as an equally remarkable gourmet. He used his table as a weapon of diplomacy and his French-style service was literally listening to his guests: a valet was responsible for pouring drink, removing the empty glass, and serving the dishes all arranged on the table together and at the same time. The valets attentively and patiently listened to their master of an evening’s words and scrupulously reported to Talleyrand the next day what had been said at the table the day before. It has been said that “the only master Talleyrand has never betrayed is Brie cheese”.

An anecdote about Talleyrand: the year of 1803 was extremely cold with a long winter. This weather made fish rare and therefore expensive. Talleyrand received two salmons of an extraordinary size, when the first appeared, the guests were enthusiastic at the sight of this fish in majesty, then were sorry when the salmon fell to the ground, the waiter having tripped on the carpet (by order of his master) and Talleyrand, imperial, simply said: “Let another one be brought to us”, which was done.

The reign of Napoleon saw the rise of French haute cuisine and the first celebrity chef, Marie-Antoine de Carême known as “The King of Chefs, and the Chef of Kings”, who worked for Talleyrand during the reign of Napoleon, then the Prince Regent in London (later George IV), very briefly for the Tsar Alexander I, and later the banker James Mayer Rothschild from 1824 to 1829.

Antoine (or Antonin) was born into a large French family in 1784. His father abandoned him on the outskirts of Paris at 8 years old, wishing him to find a way through life on his own. Luckily, the boy was hired by an innkeeper, who employed him as a kitchen boy. At 13, he became an apprentice for a renowned pastry chef, Sylvain Bailly. Antonin was lively, curious, and very talented, and his master encouraged him to develop his talent. In particular, he allowed his young apprentice to go often to the library, where he discovered a passion for architectural and landscape plans, from which he elaborated constructions, sometimes several feet high, made entirely out of foodstuffs such as sugar, marzipan, and pastry, the famous “pièce montée”. He opened his shop, the Pâtisserie de la rue de la Paix, where he showcased his creation behind the window.

Carême was set a test by Talleyrand: to create a whole year’s worth of menus, without repetition, and using only seasonal produce. Carême passed the test and completed his training in Talleyrand’s kitchens.

His influences on cooking were several, in the development of a new refined food style using herbs, fresh vegetables, and simplified sauces with few ingredients. And he changed the head covering of the cooks named originally “casque à meche” (stocking cap), in to the modern toque that we know today. He created a classification of all sauces into groups based on four mother sauces, he called them Grandes et Petites sauces (Great and small sauces), in his book from 1833, « L’art de la cuisine française au XIXe siècle ».

Antoine-Marie Carême imported an aesthetic and a real art of the table, he paved the way for the development of what is today called “haute gastronomie”. It is not just about being a great cook, it is also about having the eyes of an artist, creator, architect. Nowadays, cooking is not one of the 7 great major arts, but there is no doubt that Carême would have been happy for it to become the 8th!

Assénat, M., Bienassis, L., & Chevrier, F. (2015). Le repas gastronomique des Français. Gallimard.

Bruegel, M. (2016). A cultural history of food : in the Age of Empire. Bloomsbury Academic.

Civitello, L. (2011). Cuisine and culture : a history of food and people (3rd ed.). J. Wiley.

Brittin, H. C. (2011). The food and culture around the world handbook. Prentice Hall.

Nair, B. B. (2021). Gastrodiplomacy in Tourism: “Capturing Hearts and Minds through Stomachs.” International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems, 14(1), 30–40.

Rockower, P. S. (2012). Recipes for gastrodiplomacy. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 8(3), 235-246.

Suntikul, W. (2019). Gastrodiplomacy in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 9, 1076.

Carème, M. A. (1828). Le cuisinier parisien, ou, L’art de la cuisine française au dix-neuvième siècle (2ème édition revue, corrigée et augmentée). Chez l’Auteur.